by Jeevika Vivekananthan

Vankkam. Wominjeka.

I am a Tamil diaspora woman living on the land of Wurundjeri people. I acknowledge the elders past, present and emerging for their wisdom and the resistance against all forms of oppression. Even though I come from a war-and-conflict-affected Tamil community in the North of Sri Lanka, I acknowledge my positionality as someone exposed to both the Global South and the Global North, using North and South labels in a metaphorical distinction to denote an entire history of colonialism, neo-imperialism and geopolitics. I am not an academic nor an expert. As a toddler researcher, I recently presented a reflection piece at a conference hosted by the Development Studies Association of Australia in Melbourne, reflecting on my journey from a student researcher to a researcher. This is the written script of my presentation, slightly modified for the purpose of publication at Convivial Thinking, encouraging the readers to contest and reflect on the concept/ practice- the ‘naked’ researcher.

During my postgraduate study in Melbourne, I explored ‘diaspora in development’, conducting qualitative research on ‘The role of Tamil diaspora in knowledge-based development of post-war Northern Sri Lanka’. The discourse on diaspora in development is not inclusive of the voices of the local counterparts of diaspora actors from Global South. I was really excited because I was focusing on the missing part of the discourse- the local voices. There was another reason for my excitement- I was going ‘home’.

It was the time for a fieldwork visit to Northern Sri Lanka. I filled the ethics application in a way it wouldn’t be addressed as a higher than lower-risk application to save me some hassle. My understanding of ethics four years ago- explain the Plain Language Statement and Consent Form (PLSC) to participants and get their informed consent. Pretty simple and straightforward right?

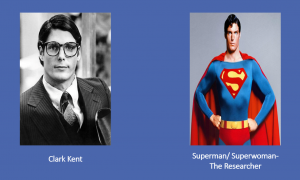

It was 2016 January. I flew home. Despite the person I was, the one who had hands-on experience of war and conflict and could empathize and reciprocate the feelings of my fellow Tamils, I found a Superwoman in myself. Remember Clark Kent?

Photo source: https://fierofredo.wordpress.com and /https://www.eightieskids.com

Who was I to my participants? The researcher- the superwoman? An insider sharing the same social location with participants? Or an outsider who left the country two years before?

Positionality explains the researcher’s social location in relation to the researched, the ‘others’. Some researchers identify themselves as insiders because they belong to the community which is under the study. Some researchers, mainly from the Global North, identify themselves as outsiders when they research a community in Global South which they do not belong to. In anthropological studies, some researchers position themselves in between insiders and outsiders. The argument is that one does not need to be a member of the community to have knowledge of it. Positionality is spatially and temporarily bounded.

My position was rather multifaceted. The research was about the role of Sri Lankan Tamil diaspora whereas the inquiry focused on the perspectives of the local Tamil community in the North. I migrated to Australia in 2014. I started mingling with the Tamil diaspora community in Melbourne. Meanwhile, I kept my personal ties with the local community as strong as ever through frequent communication and updates. I also briefly visited Sri Lanka in August of 2015. Therefore, you can position me in between the insider/outsider continuum, but closer to the insider position rather than taking an absolute central position considering the advantages of having an intimate knowledge of the targeted community and close contacts with them. I acknowledge that some of the research participants embraced me as an insider while others perceived me as an outsider who left the country. It’s a mix.

Regardless of being perceived as an insider or outsider, I was this superwoman, a female version of Clark Kent, wearing an invisible cloak, going to the community, thinking that I was doing them a favour by giving them a platform to voice their opinions about their diaspora counterparts in development. You wouldn’t believe how professional I was. And I was confident that I was ready for this task.

I sat with members of the local civil society organisations for doing the research interviews. Most of them were very welcoming and happy to accommodate me during their busy schedules. They had many stories to tell, sometimes very personal stories, not necessarily the answer to my research questions. Of course, I listened, that’s what I thought. I did not realise the vulnerability I have placed them in. I did not realise it was a privilege to listen to their personal stories. I did not realise the power of stories that could have changed the direction of the research. My mind was either plotting for the next question or trying to connect the dot-points in their narratives. I am ashamed to listen back to the interview audios. I listen myself jumping in the middle of their responses, cutting off the flow of their stories, asking questions that I thought important for the research. I see myself desperately holding onto this invisible cloak- despite the slips now and then that were either intentional or accidental. Nonetheless, I did my best as a Superwoman- masking my emotions, not empathizing and not reciprocating their feelings where I should have, and I should have been vulnerable as my participants in those moments. I did not! I wrapped up my field-trip and left with the data. Thesis writing was overwhelming. All I wanted was to convince my academic reviewers. One was highly convinced whereas the other one was very critical about my writing or, in other words, my English language proficiency. Their grading was contradicting each other’s so the panel had to bring a third reviewer. I got a distinction for the thesis which I have hard-time opening these days. Confession time- I did not share the findings with my participants, the ground-breaking knowledge about how local actors perceive their diaspora counterparts in post-war development. It is trapped in my thesis and in my guilty mind. What have I achieved as a researcher with such boundary-maintaining process in the knowledge production?

Constructivist approach was my theoretical paradigm to guide the research process. Constructivism defines the nature of knowledge as individual and collective reconstructions. The knowledge accumulation is in the form of a more informed and sophisticated reconstruction of vicarious experience. This approach suggests co-constructed realities and co-created findings on the basis of relativism. Sounds fancy right? What’s the missing part of this paradigm that failed me becoming a passionate participant in knowledge production? Is it a result of wearing the cloak which I inherited from my exposure to Global North, its idea of scholarly knowledge, academic research, professionalism, distance-maintenance and data-oriented extractive research practices? Why wasn’t I informed by the paradigm about the importance of trust and relationship with historically disadvantaged yet resilient communities who have their own voices, stories and their way of understanding the world? I would call it as an epistemological injustice.

At this point, I want to acknowledge Kalyani Thurairajah, a Tamil diasporic scholar, for her Superman analogy and her scholarly contribution to the discussion on the boundary- building and breaking between the researcher and the participant. She discusses the ethical consideration of boundary un (making) process within an insider/ outsider research framework (Thurairajah 2019). I am adopting her analogy to discuss the relationship between a researcher and the participants.

She presents 3 scenarios:

Fully cloaked researcher- maintains a strong boundary with his/ her participants and refuse to share positionality and social location. The information flows in one direction, and the participants are encouraged to be vulnerable.

Strategic undressing- boundaries are not as thick as with the fully cloaked researcher. Here the researcher chooses to reveal some of his/ her identities and social positions, not necessarily done to ensure ethical practice but to ward off any suspicion. Trust is not necessarily built on mutual honesty. Therefore, ethics can be blurry.

Naked researcher- does not maintain boundaries with participants and shares positionalities and social locations all the time, including continuous reflections on how his/ her positionality that shape the relationship with participants. Here mutual trust and faith are required. Researchers become the participants by forming genuine relationships; in doing so, the researchers would also be revealing their outsider positionalities and the ways in which they are different from the participants. They become vulnerable as their participants in this process.

To address the epistemological injustice, let’s think about becoming these ‘Naked Researchers’- is that even possible? No boundary maintenance- genuine relationships- a consistent practice of reflexivity of discomfort- the discomfort of the cloak of power and privileges- is it possible for researchers to become vulnerable, self-critical and willing to be challenged, and to change during the research process?- more than anything be accountable to communities that we create this new knowledge with?

I would like to acknowledge the Pacific methodologies I was exposed to as part of my next research on Pacific diaspora in humanitarian response to disasters:

Fonofale

Teu le Va

Talanoa

What is it these Pacific methodologies suggest different to Western methodologies?

‘Intricacies for deeper, meaningful relationships to be formed.’ (Ponton 2018)

These methodologies inform us to cherish, nurture and take care of the relationships, recognise the collective approach to life and allow researchers to enable participants’ voices and stories to be foremost in the knowledge production.

Now I’ll tell you my attempt of becoming a ‘Naked Researcher’ to an extent, losing the cloak one slip at a time, reflecting on the power, privileges and the agency I had as a researcher. The purpose of the next research is to understand why and how Pacific diaspora communities in Australia support their families and communities in times of disasters in Pacific island countries. The research was initially designed to analyse cross-perspectives on Pacific diaspora humanitarianism; perspectives from Pacific diaspora itself and the traditionally recognised humanitarians. I visited this renowned international humanitarian organisation at the beginning of our research. Even before I finished explaining the research topic, this person who was in a managerial position and responsible for the work in the Pacific told me ‘Oh tell them (Pacific diaspora) to stop sending goods’. Well for real? I think, at that point, I realised my agency as researcher. I was reminded that this was going to be more than an act of knowledge production when knowledge production a political act itself. The mainstream humanitarian actors spoke so loudly and confidently about Pacific diaspora in UBD (unsolicited bilateral donation). Pacific diaspora was perceived as a source of UBD or either remittance. What’s the missing part of this knowledge? In whose view we are going to define what Pacific diaspora humanitarianism is? Our research showed us how little the traditional humanitarians know about Pacific diaspora actors in disaster response. How do they then get to define Pacific diaspora humanitarianism? Citing this as a methodological injustice, we separated the data.

On the other hand, as an outsider, I was really struggling to make a connection with the Pacific diaspora community. All these talks about Pacific diaspora being invisible, and I was at a point of losing my perseverance and buying into that narrative. Then I met a Fijian diaspora in Melbourne who pointed out what was wrong with my approach. He showed me how to communicate our research in a simple language without overwhelming and intimidating community participants. That was an eye-opening demo and a turning point in our research. This research has taught me that Pacific diasporas are not the ones who are invisible; it’s us in the academic and humanitarian circle, building a wall of power and privileges around us and speaking a different language, and we the emperors looking over our walls and say our peasants are invisible. The problem lies with us; our systems, values and language.

Thanks to the Centre for Humanitarian Leadership for giving this research more time to create a good rapport with the diaspora participants. Our research interviews, I would like to call them deeper and meaningful conversations, ended up in warm hugs, emotional farewells at railway stations and a lot of memories to look back. I became a good listener. I was fully present in the conversations and I did listen this time. Pacific diaspora participants shared incredible stories and feelings about families and communities, survival and resilience and communal responsibility and solidarity. They also talked about their frustrations with researchers who use them for obtaining information and leave them with nothing in return. It hit me home. I was there and I have done that.

Our research report- ‘Crossing the Divide: Pacific diaspora in humanitarian response to natural disasters’– was published a few months ago, featuring the voices of Pacific diaspora community leaders, presenting their perspectives, publishing their names on the acknowledgment page besides Phil Connors, my co-author, and myself, and requesting the readers to recognise the contribution of the diaspora participants in the research findings as well as the report. I kept in touch with the diaspora participants and sending post-research updates. Whenever I was approached for contacting diaspora participants for other researches, I insisted on knowing what’s in it for them. I asked the diaspora participants if they would like to be involved. I refused to take advantage of the trust I have built with them. As a researcher, even after you wrap-up your research project, you will encounter situations where you need to stand up for your research participants and their community by quoting the new knowledge. I have taken that upon myself. I have also seen that some of our research participants have been empowered to do the same from their side. This is a co-responsibility. I still keep in touch with some of the Pacific diaspora leaders whose one phone call away to consult on the topics that involve them and of which I acknowledge I am no expert. No, we do not become community experts after doing research about a community. We may feel like we are insiders but we are all intruders!

What I have explained here is not much. Not 100% participatory. Not 100% of becoming a ‘naked researcher’. It is a good attempt, though, by slipping the cloak of power and privilege and becoming a participant in the knowledge production and dissemination. I argue, thus, a researcher in the qualitative research tradition of social sciences, especially when you work with historically disadvantaged communities in a development or humanitarian research, should become an active participant of the knowledge production and dissemination by slipping the cloak of power and privileges as well as practising the reflexivity of discomfort.

Jeevika Vivekananthan is currently working as a research assistant at the Centre for Humanitarian Leadership with a particular focus on ‘Pacific diaspora humanitarianism’ and ‘health diaspora in humanitarian health’. As a social researcher, Jeevika is interested in different worldviews, looking beyond mainstream for untold stories and attempting to overcome the epistemological injustices of colonialism, neo-imperialism and geo-politics in development and humanitarian studies. She welcomes comments on this reflection piece. Please contact Jeevika at jeevika@cfhl.org.au

Thank you for sharing your research jouney experiences Jeevika. Interesting reflection on your experience! I must say, my heart sank as I read your confession. I cannot and will not judge you, as I am only studying research methodologies now and will hopefully get to that time of conducting research. Your reflections helps me clarify certain concpt and ideas, ie Naked researcher, who I hope to be. It has provided me another practical way to express what Christina Bettez terms “stiving to centralise communion” as a reseacher. Furthermore, she (Bettez) shows how complexities brought about by the hyphen in Insider-Outsider requires more interrogation, which I think you contribute by introducing continuum instead of hyphen. Lastly in her navigation of complexities of qualitative research in post-modern contexts, she shows how that naming positionality also carries a risk of excluding and oveshadowing certain aspects.