by Romina Istratii

Recently, I participated in a panel that was convened at LSE dedicated to the topic of decolonising African knowledge systems. The panel members, who included also Prof Akosua Adomako Ampofo from the University of Ghana and Dr Wangui wa Goro, were invited to trace the progress made to-date in decolonising Africa’s knowledge systems and to explore how these systems may be rethought, re-framed and reconstructed to rid them of the hegemony of western Euro-centrism. I’d like to share some of the key points of my presentation with the network of Convivial Thinking to call for a more organised effort toward decentring the current epistemology.

In both my presentation and more recent activities at SOAS, I sought to underline that the persistent dominance of western European epistemology is inevitably intertwined with the more material, structural and normative realities of research development and scholarly publishing, which need to be subverted in parallel to achieve some sort of epistemological pluralism. I am speaking informed by a decade’s experience working as a critical international development researcher and practitioner, more recent experience in research development and funding and open access publishing, and with the hindsight of about three years’ engagement with the decolonising SOAS working group. As an Eastern European coming from a low-income family of first-generation migrants to southern Europe, I appreciate deeply the importance of being able to produce knowledge and to access the one available, and I am especially keen to subvert barriers that still make this difficult for some populations or groups.

On-going epistemological hierarchies with colonial undertones

The problem of western epistemological dominance features in most conversations nowadays, but epistemology is rarely explicitly defined. In my usage of the term, I echo Gloria Ladson-Billings’ understanding that “[e]pistemology is ultimately linked to worldview” (2005, 258) to stress that individuals are always situated in a belief system that they have reasons to value and that their ways of reasoning and validating what they know is never disconnected from who they are and the beliefs they hold. Historically, the Western European colonisers projected their worldviews, interests and understandings of humanity onto the ‘other’, as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o has thoroughly conveyed in Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986, especially p. 16). In contemporary times, a lack of recognition about the epistemological situatedness of historical paradigms and limited reflexivity about personal positionality in research and theory-making combine to perpetuate western European or other hegemonic assumptions in knowledge production.

The workings of western Euro-centrism within scholarship have been discussed many times before, but I‘d like to highlight three trends pertinent to this discussion: theory-making that is not empirically grounded, dominance of English language in learning, teaching and research, and Anglophone standards and norms dictating mainstream knowledge production. Having grappled with western Euro-centricity in development theory and practice for a decade, I consider disconnects between theory and real communities of people to be the most alarming. I believe that this reflects a more fundamental perversity underpinning western epistemology – a conceptualisation of knowledge that is not necessarily predicated on human experience. This is amplified by the equally problematic dominance of English language in learning, teaching and publishing research, which discourages engagement with scholarship in other languages and contributes to neglecting non-western conceptual repertoires and understandings of the world and humanity. This system is completed by western Euro-centric standards of knowledge validation (‘politics of citation’) and understandings of research excellence and impact, reflected best in peer review norms and standardised modes of publishing and knowledge diffusion.

These epistemological issues should not be disconnected from more structural, material and normative realities that influence scholarly knowledge production in the UK and internationally. Multiple conditions, incentives and pressures converge to ensure that these trends persist, including political and ideological agendas governing scientific research and production in industrialised societies where the majority of funders are located, research funding availability, structures and regulations, publication models, and attitudes among researchers.

Distribution and trends in research funding

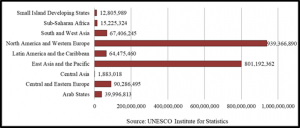

A rough look at funding data shows that research funding has been disproportionately available in the world, with North America and Western Europe displaying the highest Gross Domestic Expenditure on Research and Development (GERD). In 2016, of the world total, 0.7 percent appertained to sub-Saharan Africa and 46.5 percent to North America and Western Europe. While the level of funding reflects the size of the economy and the relevant sectors of each country, justifying differences in numbers, the fact remains that funding for research has been unequally accessible to researchers across the world. One study suggests that the share of global R&D accounted for by Asia, Latin America and Africa increased since the 1970s, but without significant reduction in global inequalities (e.g. Arond and Bell 2009, 23).

Table 1: Gross Domestic Expenditure on Research and Development (R&D) in ‘000 current PPP$, 2016

In recent years, research funding seems to have become steadily more focused and has expanded in scale (Blotch and Sørensen, 2015). For example, in the UK, the emergence of ODA-related funding through schemes such as the GCRF and the Newton Fund means that funding has been increasingly targeted at DAC-listed countries and has encouraged the development of research centres/networks to achieve more interdisciplinary and impact-oriented research. In parallel, historical criticisms around conventional OECD aid models and pressures at home for more transparent use of charity funds and data management following various scandals, has fostered an increasingly bureaucratised research funding process. Subsequently, research development and bidding has become more ‘institutionalised’, creating additional inequalities since institutions that do not have the capacity to support the research development process are unable to apply competitively for these grants.

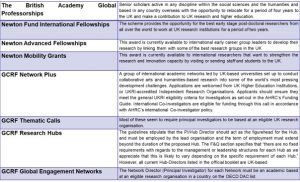

On the other hand, schemes that fund international research tend to favour institutions and researchers based in western societies, which reflects both the location/motives of the funders and the rules of funding disbursement and due diligence. For example, a closer look at select international-looking UK funding opportunities and their eligibility criteria evidences that for the majority, principal investigators (PIs) must be based at a UK institution. A number of these enable scholars from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to come to the UK, and in some exceptional opportunities, such as the GCRF Global Engagement Networks, it is stipulated that the PI must be from an LMIC country.

Table 2: Select international-looking UK funding opportunities and PI location requirement

While it is justified that UK research funding be allocated primarily to UK-based researchers, it is problematic that research that presumably aims to support LMICs in addressing development problems places so much material (and, inevitably, epistemological) power in the hands of the UK-based PI. Both their focus on global challenges and critiques that the SDGs do not necessarily reflect local priorities make it all the more urgent for local researchers (ideally from diverse backgrounds) to lead such efforts. Funders do recognise this to some extent, but might still argue that accommodating this can be difficult in view of lack of local universities’ capacity to administer funds in ways that match their strict guidelines of post-award management and due diligence.

Conversely, funding that brings scholars to the UK may arguably eschew issues of ‘brain drain’ by stipulating that scholars return to their societies after a period of time, but they do not resolve western Euro-centrism. As most could attest, being located in a western university and having to converse with western epistemology, even if briefly and marginally, makes a degree of co-option inevitable. Moreover, there is no guarantee that the potentially different viewpoint of the LMIC scholar will be received with openness in deeply ideological academic circles.

The core-periphery structure of global academic capital

These funding asymmetries and norms exist alongside an equally problematic publishing landscape. A colleague from Hungary, Márton Demeter (2019), previously analysed the geographic distribution of authors in leading periodicals indexed in the Web of Science’s SSCI list. Márton found that between the years 1975 to 2017, the number of Global South academics succeeding in publishing in core periodicals varied from 1 to 10 percent, with researchers in the Global North contributing up to 85 percent of world knowledge production. In this case, the Global North incorporated the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, the UK, Western Europe, Israel and some Asian countries, while the Global South included Latin America, Eastern Europe, most Asia, the Middle East, Africa and parts of Oceania.

His findings are not the only ones and other studies confirm this problematic distribution. What needs to be recognised, however, which Márton thoroughly elaborated in his excellent analysis, is that this distribution is connected to the geographical location and the language of mainstream publishing houses, peer review standards and journal impact metrics, which cumulatively enforce the core-periphery geographical and socio-economic stratification that he found in the distribution of scholarly output.

Implications for research and researchers in LMICs

Most of these implications were discussed at a recent event at SOAS, which attempted to apply a decolonial lens to research development structures, practices and norms (a full report has been published by the SOAS Research & Enterprise Directorate). To highlight a few, I will draw from the testimonies of our international participants on the day.

As Prof Achille Mbembe has pointed out for African universities (2016), in most countries higher education has been structured under the influence of a western model: assessment-based, productivity-based and evaluation-based. In contrast to western academics with full-time jobs or secured research funding, most non-western researchers do not have protected time for research and are based in institutions facing capacity limitations. This means that researchers in LMICs have high incentives to become part of international research projects to further their research interests.

However, this can place them at a disadvantage due to the material and structural inequalities discussed. Not only might they not be properly attributed for their work, but they may also be treated only as ‘data collectors.’ Conventionally, knowledge-sharing has tended to be mono-directional with western European researchers dominating discussions and setting the agenda. This has meant a neglect of local languages, knowledge systems, ontologies, methodologies and axiological systems, as Prof Alex Kanyimba from the University of Namibia put it during the event we held at SOAS.

Dr Mulugeta Berihu from Aksum University in Ethiopia furthermore pointed to the limited commitment on behalf of western partners to contribute to local capacity-building in the context of research projects, endangering their continuity and sustainability. Dr Seira Tamang from Nepal, in turn, spoke about the fact that local researchers are often constrained in their ability to publish the outputs of these international projects for local impact, which can reflect funder rules around data use, contract restrictions by western publishers, combined with power hierarchies between UK-based and local researchers.

On the other hand, the very tight deadlines of internationally-looking funding calls in combination with their requirements for interdisciplinary research can incentivise bad practices in the development of international partnerships. For example, prominent institutions in local countries might be consistently favoured, fostering the marginalisation of regional universities, small research institutes and non-academic institutes.

Some practical suggestions forward

These issues are neither comprehensive nor categorical – the reality is considerably more nuanced than a blog essay can delineate. However, it is clear that there are important structural, normative and practical issues that need to be addressed simultaneously. As I argued before, measures to reverse these can be taken by all the parties involved, including funding bodies, research offices and institutions or researchers in the UK and internationally.

For example,

- funders might consider how to accommodate multi-vocal narratives in the conceptualisation of calls or engage local researchers of diverse backgrounds in the review of international research projects.

- Research development offices in western institutions can liaise with their local counterparts and provide support where needed and to become more sensitised to local research conditions.

- Universities in the UK could provide different incentives to their academics to encourage reflexive research practices (e.g. by rewarding transparent budgeting practices or language acquisition).

- More collaborative peer review processes could be instituted between European and local institutions to assess relevant project proposals and to ensure that these are sufficiently grounded in local realities and conditions.

Revisiting the fundamentals of knowledge production

Still, these measures need to be combined with a more profound reflection on the meaning of knowledge and the role of universities and scholarship in society, a point that was raised also by Akosua and Wangui during discussions with the audience at the last panel. First and foremost, we need to consider more seriously whether and how different understandings of knowledge can be accommodated in institutionalised research and knowledge production and what it might take to achieve this.

In this light, I would urge a reconsideration of standards of ‘excellent’ research and what makes a ‘good’ researcher or academic to move toward a model that places personal reflexivity and ethos higher than qualifications and publications. As Akosua rightly pointed out, education is not only about learning the sciences, but also about cultivating values to become good people. I like to tell my own students that as instructors we are not here to tell them what to think but how to think critically and reflexively about the world, but this requires authentic humility in engaging with others and openness to life-long learning.

Lastly, as someone trained in multiple languages and having recently set up my own voluntary study group to help second-generation Ethiopian students improve their Amharic (while maintaining and refining my own!), I am convinced that it is essential to reconsider the role of language learning and teaching in decolonising higher education and explore how multilingualism might be structurally accommodated in research development processes and international collaborative research.

Imagining alternative futures

In my LSE talk, echoing Prof Achille Mbembe, I stressed the need for structural, normative and trans-boundary/collaborative initiatives and approaches. I believe that we all have a stake at seeing the system change and that we can all contribute to this effort. This conviction has fuelled my own dedicated work (together with my colleague Monika Hirmer and a team of international collaborators) in the past two years to set up Decolonial Subversions, a multilingual, free-of-charge publishing platform that seeks to subvert more systematically some of the norms and barriers discussed, from language requirements to peer review processes to citation politics. The website and the initiative will be launched soon in the context of a series of activities at SOAS dedicated to the decolonisation of the university.

However, such initiatives are life-consuming and require the right attitude and ethos to inspire others and to be sustained. As Monika and I noted a few years ago when as PhD students at SOAS we were producing the Decolonisation in Praxis volume , decolonising knowledge is first and foremost attitudinal: to embody humility and openness in all our engagements with diverse communities and to recognise that “we have no authoritative grounds for imposing our worldviews as normative on our interlocutors” (Istratii, Hirmer and Lim, 2018, p. 9).

Dr Romina Istratii is Senior Teaching Fellow to the School of History, Religions and Philosophies and Research Associate to the Department of Development Studies and the Centre of World Christianity at SOAS. She is a critical international development thinker and practitioner with a decade’s experience in the field, currently teaching and researching at the intersection of gender, religions and development from a decolonial perspective. Since 2016, she has been involved with the Decolonising SOAS Working Group and more recently she acted as a Research Funding Officer for the SOAS Research & Enterprise Office, in which role she set up the Decolonising Research Initiative.